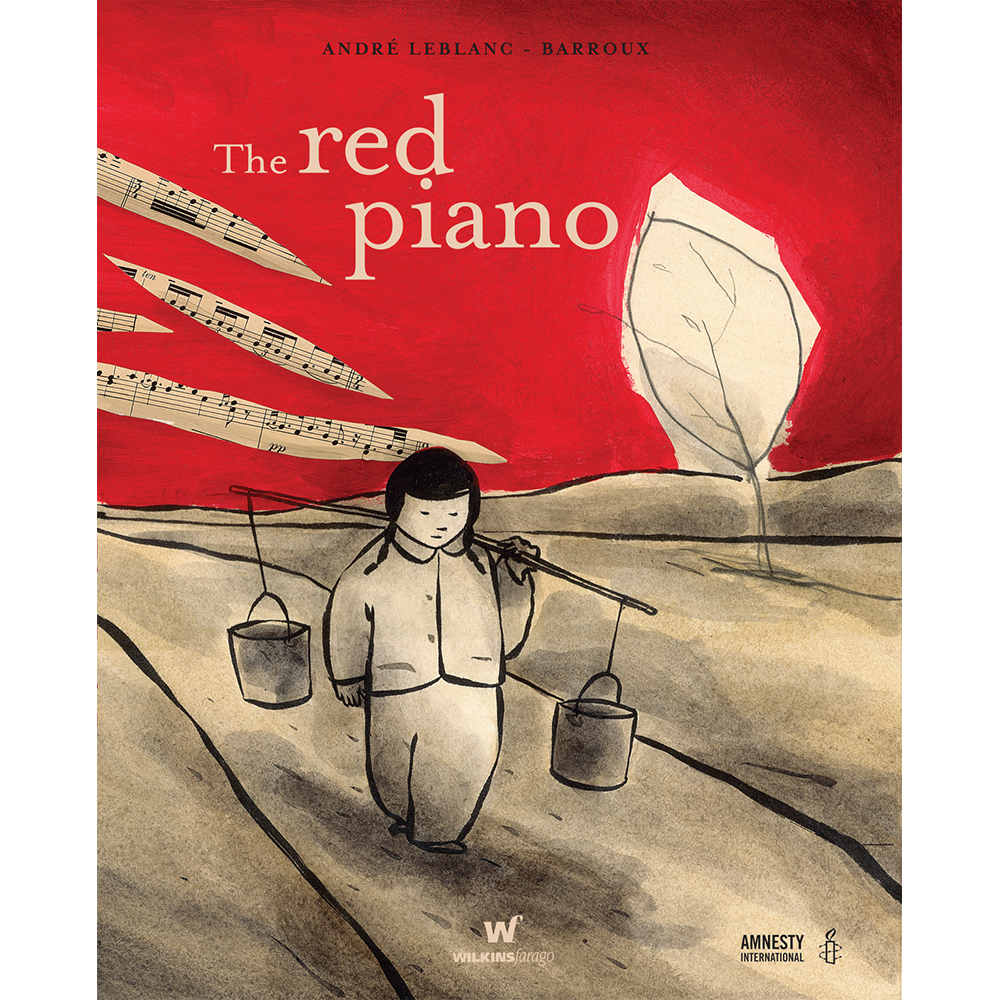

This stirring and beautiful picture book relates the moving and inspiring story of a gifted young girl’s passion for the piano in a time of historic turmoil.

During China’s Cultural Revolution (1966 – 1976), a young girl is taken from her family and sent to a far-off labour camp.

Forbidden to play the piano, she nevertheless finds a way of smuggling hand-written music into the camp and sneaking away at night to practice a piano in a secret location.

Then, one night, she is caught …

Inspired by the amazing true story of the international concert pianist Zhu Xiao-Mei, Andre Leblanc and Barroux‘s acclaimed picture book from France poetically relates an extraordinary story of perseverance set against a cataclystic period of history which is, to this day, still shrouded in mystery.

Book Trailer

Reviews

“This is a magnificent book in every respect.”

~ Magpies Magazine

“A must for any child’s bookshelf.”

~ Amnesty International Journal

Teachers’ notes and student activities by Helen McIntyre

About the book

This stirring and beautiful picture book relates the moving and inspiring story of a gifted young girl’s passion for the piano in a time of historic turmoil.

During China’s Cultural Revolution (1966 – 1976), a young girl is taken from her family and sent to a far-off labour camp. Forbidden to play the piano, she nevertheless finds a way of smuggling hand-written music into the camp and sneaking away at night to practice a piano in a secret location.

Then, one night, she is caught …

Inspired by the amazing true story of the international concert pianist Zhu Xiao-Mei, Andre Leblanc and Barroux’s acclaimed picture book from France poetically relates an extraordinary story of perseverence set against a cataclystic period of history which is, to this day, still shrouded in mystery.

About the author

Andre Leblanc

Artist and historian Andre Leblanc’s chance meeting with the celebrated international concert pianist Zhu Xiao-Mei inspired him to tell the story of her childhood in China during the Cultural Revolution. The book that resulted is The Red Piano.

Andre has taught most of his life, as a school teacher and then as a Professor of Art History. He has also devoted part of his career to painting and photography and has exhibited in both France and Canada. He lives in Montreal, Canada and is also author of several non-fiction works for children.

About the illustrator

Barroux

Illustrator of The Red Piano, Stephane-Yves Barroux was born in Paris, France, and grew up in North Africa. He came back to France to study photography, art, sculpture, and architecture at the famous art schools, Ecole Estienne and Ecole Boule, for several years. He went on to work as an art director in Paris, Montreal and New York. He also worked as a press illustrator for numerous papers such as the New York Times, Washington Post and Forbes magazine.

Barroux is now well known for his illustrations for children’s books, both in France and the USA. Driven by his love of colors and fantasy, Barroux works on his illustrations traditionally, using linocut, acrylic painting, lead pencil, and collage. In 2005 he received Switzerland’s prestigious Enfantaisie Award for Uncle John and the Giant Cherry Tree.

Discussion points and questions for teachers and parents

The reading of The Red Piano and the completion of the following activities will assist students to:-

- Understand Asia

- Develop informed attitudes and values

- Know about contemporary and traditional Asia

- Connect Asia and Australia

- Communicate effectively

(National Statement for Engaging Young Australians with Asia in Australian Schools, 2006. http://asiaeducation.edu.au/index_flash.htm)

PRE-READING QUESTIONS & ACTIVITIES:

Show students a map of China, and its place in relation to Australia. Are these large countries in the same hemisphere? Can they find out how many hours flight time between Melbourne and Beijing, and between other Australian capital cities and Beijing? Point out Beijing and then the Chinese province of Inner Mongolia where the story is set.

Do a Venn Diagram class brainstorm to establish the prior knowledge of students. Label one circle Chinese history, the other circle China today. The intersection of the two circles will provide space for students’ knowledge about China which fits both labels. This brainstorm will establish any knowledge of Mao and the cultural revolution. The Historical Note box on the page adjacent to the title page of ‘The Red Piano’ can then be utilized by teachers.

Text: Chinese characters are used to signify the ‘çhapters’ in The Red Piano. These are presented in the ‘chops stamp’ style, reminiscent of imperial seals. Chinese characters are also present in several illustrations. If you have Chinese students in your class, ask them to teach the characters for the numbers 1 to 10. Also ask them to teach some other basic characters and explain the pictograph basis to the composition of many characters. Otherwise….Teach students to write their own name using Chinese characters.

Narrative style characteristics: Explain to the students that the narrative is written in the third person. Show students an excerpt from the autobiographical The Chinese Cinderella by Adeline Yen Mah (1999), and compare the first person ‘I’ voice style.

Narrative style characteristics: The main character’s name, ‘the young girl’, is not revealed to the reader. This will be further explored in the activities.

Vocabulary: culture, elitism, revolution, curfew, comrades, communal house, latrine, accomplice, Bach, Bach prelude, Communist Party, re-education, arpeggios, cadences, counterpoint, staves.

DOUBLE PAGE BY DOUBLE PAGE QUESTIONS & ACTIVITIES:

There are 16 double page spreads in the book.

Students should write full sentence responses, unless otherwise instructed.

The questions and activities connect to English, SOSE-Humanities and The Arts.

- Zhangjiake Camp 46-19 on China’s border with Inner Mongolia is blighted by an eerie moonlight.

By using the words blighted and eerie how is the narrator trying to make the reader feel? You may need to look these words up in the dictionary.

How does the illustration add to this feeling? Comment on the use of colour.

Does Camp 46-19 make us feel that there must be just a few camps, or many camps? Why?

- Taking small careful steps the young girl leaves the communal house….she can already make out the house of her accomplice, Mother Han.

Which word tells us that the two main characters, the young girl and Mother Han have embarked on a forbidden quest?

Make a list of the phrases in the first paragraph which inform the reader how unpleasant the camp conditions are.

Create a ‘sense wheel’ by drawing a circle with 5 even segments. On the outside of the circle label each segment with one of the senses: touch, taste, sound, sight, taste. Inside each segment write quotes from the text for the appropriate sense.

How does the illustration add to this feeling? Comment on the use of colour, as well as the body language and facial expression of the young girl.

Extension question: What is the illustrator, Barroux’s, intention when the only colour in the illustration is the red armband? (Stephen Spielberg uses this technique in the depiction of another sad, lost little girl in the black and white film Schindler’s List).

Double page illustration – no text.

What is the story-teller’s intention in presenting this double page illustration of the tree- lined path and the small figure of the young girl on her quest? Why is there no text?

Do the pages successfully communicate to the reader? Does the reader feel like they are stepping into the shoes of the small girl? If so, how?

What is the effect of the long shadows and the large trees? What do they tell us about the psychology of the small girl?

Thoughts go back to her previous life……..She leans forward, her frail body lost in her blue jacket, her plaits brushing against the keys and without waiting any longer, she launches into her Bach prelude. Warmth returns.

Here the writer is not only literally telling us what the young girl wears – a blue jacket – but is also symbolically telling us about a period of history in China when everybody wore Chairman Mao’s blue suit. Therefore the writer is also symbolically telling us how she felt during this period of re-education, that is, ‘lost in her blue jacket’. How many years has the young girl ‘been lost’. Why? What gives her comfort?

What is the literal and symbolic meaning of the phrase ‘warmth returns’? Ask your teacher to tell you about emotional intelligence and the role of music.

Draw up 2 columns. Label one ‘Camp 46-19’ and the other ‘Mother Han’s home’. List your observations about each setting. Think about how they compare and contrast to each other.

What is a Bach Prelude? Who was Bach? Why was Bach’s music a problem in the Cultural Revolution? (The Historical Note about the Cultural Revolution at the beginning of the book will assist teachers here.) Ask your teacher to play you some Bach music.

Why does Mother Han take the risk of having a piano in her home, and encouraging the small girl to play? What rewards might this bring Mother Han? The illustrations will help you here.

By now readers will be very conscious that the illustrations in The Red Piano are restricted to the colours, black, grey and red. Often in China, black means darkness and winter, and red is the colour for weddings. Red is associated with the sun and represents happiness and celebration. * Politically, red is also associated with Communism. In the 1950s, when this story takes place, China was known as Red China.

Taking all this into account, what might the illustrator be intending with the red backdrop to the events shown on this double page?

(*Dragon Emperor Treasures from the Forbidden City, M. Pang, 1988, pp 22-23)

Pianos are criminal. Schools are closed down. The Communist Party is re-educating everyone.

What are the beliefs of the Communist Party at this time, and how have they gone about re-education in China for the past 5 years?

From sunrise to sunset she has to learn a new way of life… The Great Chinese Cultural Revolution continues.

We know that the young girl’s previous education was in a gifted young musician’s program in Beijing. What is she learning now?

We still only know the story’s heroine as ‘the young girl’ and ‘she’. We have no name and her face has no detail. Why might this be so? What might the writer and illustrator be signifying?

Is it reasonable to require children to write letters of self-criticism each night?

Is anybody in China required to write letters of self-criticism by the police today?

Her fingers fly across the keyboard. ..Bringing a piano all the way here. What a crazy venture.

Look at a chart of the 16 Successful Habits of Mind. They are: Perseverance, Resilience, Questioning and Posing Problems, Managing impulsivity , Listening with Understanding and Empathy, Thinking Flexibly, Thinking about Thinking, Striving for accuracy and Precision, applying Past Knowledge to New Situations, Thinking and Communicating with Clarity and Precision, Gathering Data Through All Senses, Creating, Imagining and Innovating, Responding With Wonderment and Awe, Taking Responsible Risks, Finding Humour, Thinking Interdependently, and lastly, Remaining Open to Continuous Learning.

Which Successful Habits of Mind does the young girl demonstrate on these pages? In pairs, for each Habit of Mind that you identify provide evidence/quotes in a 2 column rubric chart. Make a big chart because you will be adding to this when you get to the description of the young girl making her own music book.

- The piano travelled in a coal wagon aboard the train…a piano at Zhangjiake Camp 46-19: a miracle!

What do we notice about the train which shows that the story is set in 1950s China?

What can you find out about train travel in modern China?

Tonight she is transported back to her childhood and the muffled noise of the city. She was her mother’s great hope. Gifted at the piano…..She almost came to hate the piano.

The illustrator depicts the young girl and her parents with a lot of symbolism. We see:

*a giant Mao poster which includes Chinese characters as a backdrop

*the parents wear blue Mao suits

*the girl wears a quilted jacket with a colourful chrysanthemum flower -pattern

*the family appears happy and healthy before the Cultural Revolution

So, taking the symbols into account, what is the writer-illustrator telling us about life in China prior to the Cultural Revolution?

Why had the gifted young girl nearly come to hate the piano?

- For several years now pages from Bach’s ‘The Well Tempered Clavier’ have been passed around the camp…She decides to make her own music book.

Now you can add to the Successful Habits of Mind rubric chart which you began in Question 6. The text and illustration here are rich in showing this. Make sure you provide quotes for evidence, or descriptions of detail in the illustration.

Compare and contrast Mao’s Little Red Book and the young girl’s notebooks. Use a PMI chart for each one.

- But what possible purpose does music serve? Can it erase five years of exile?

The writer puts this question to the reader. What do you think? What part does music play in the life of your family and yourself? (See Further References: Background Briefing – Who Stopped the Music?)

Plato, the ancient Greek philosopher, said that ‘Music should be at the centre of education’. Do you agree with him? Why? Look up the latest research on the relationship between music and brain function.

- Playing for the love of music. It’s as simple as that….Last month the Philadelphia Orchestra was in Beijing. Two hundred kilometers of risk from the Mongolian border to the capital.

The illustration shows the public newspaper reading facility which advertised the Philadelphia Orchestra concert in Beijing. Newspapers can still be read like this today in China. What advantages are there?

It is curious that this orchestra from the West was permitted to perform at this time? Can you find out why it was allowed?

- Tonight in the grip of her music and her memories , the young pianist doesn’t hear Mother Han’s muffled cry. Nor does she sense the presence of intruders…Your music is not worth a dog’s fart!

What happens to Mrs Han and why?

Is there a suggestion that the guards allow themselves to enjoy the young girl’s music for a time? How can you tell? Why do the young red guards eventually insult the young girl about her music? What makes them do this? Do the colours and the frame help to explain why?

- In the morning, in front of the assembled village, she and her accomplice are denounced, lectured and insulted.

Find the meaning of ‘denounced’ in the dictionary.

What is the fate of the piano?

How is the young girl and her accomplice punished? Is public humiliation an appropriate punishment? Why?

What is a patriotic song? Can you list examples of patriotic Australian songs?

Again, only the armbands are red. What do they depict and why?

Extension: What irony does the writer want the reader to see in the events described here?

- Mother Han is driven out of the village…and the music in her heart subsides.

What jobs does the young girl have to do for punishment, and why does the music in her heart subside?

What did the guards mean when they said she was a ‘rebellious artist’?

Are there ‘rebellious artists’ in China today? Think about film, music, painting, animation, sculpture, cyber-art etc. Think about art for art’s sake like ‘the music within us all’ and also think about political art. Explain with examples.

Can you describe any rebellious art or name any rebellious artists of today?

- A year goes by. September 1976. Chairman Mao is dead… She is the last to leave Zhangjiake 46-19 re-education camp.

Here we read that she is the last to be freed from the re-education camp, and the illustration is dominated by the design of a red Mao badge. There is also a realist photo of a red guard shouting about Mao’s little red book. The camp Committee guards are sandwiched in between. What is the writer and illustrator trying to communicate here about the Cultural Revolution?

Research the Red Guards of the Cultural Revolution. How old were they? How powerful were they?

Why is this book titled The Red Piano? Why is it not titled ‘The Sad Little Chinese Girl’?

How does The Red Piano demonstrate human resilience, bravery, resourcefulness, and the power of imagination?

Extension: Research the ‘cult of Mao’ and Mao badges.

Extension: Research when the Chinese government realized that the Cultural Revolution’s quest ‘to eradicate elitism through manual labour…and by studying Chairman Mao’s political works’ had been a mistake. Which recent Premier of China was prepared to admit this to the world?

- She leaves beneath the pale light of the moon, clutching her tiny, surviving notebooks

Great writers often weave recurring symbols into their writing. What does the poetic text in this last page have in common with the poetic text on the opening page of The Red Piano?

What does the moon symbolize in Chinese stories? Why does the moon appear in the opening and closing illustrations of this story?

As the young girl hoped, classical music did survive in China. China now values classical music education for children, and some argue it is valued far more in China than in Australia.

‘Currently in Beijing, one million children are learning the violin. Across China it is estimated that between 25 and 34 million children are learning the piano’.

Is music valued in your family and your school? Explain.

- POST READING QUESTIONS and ACTIVITIES:

Amnesty International has endorsed the publication of The Red Piano. What is this organisation? What does its symbol of the candle and barbed wire mean?

What human rights aspects of the young girl’s experience during the Cultural Revolution would have concerned Amnesty International? Why?

Divide into groups and research examples of governments or groups which have tried to ban music, books, films and ideas. (Hitler’s Nazi era especially Glasnost, the Taliban in Afghanistan, Burma’s generals, McCarthyism in the USA in the 1950s, China’s current policies for her Autonomous Province of Tibet, Iran’s control of the internet after the disputed election result in 2009, ……) Present your findings in a poster for the class. Are all these examples from Communist governments, or can this happen across a variety of government types?

Visit Screen Asia at http://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/learning/screenasia/ and view the four short video clips from the documentary Vietnam Symphony. This tells the story of the Hanoi Symphony Orchestra which left Hanoi for the countryside in the 1970s during the American bombing of that city. The whole orchestra sheltered in a large underground building and continued to practise and play for the duration of the war. In contrast to The Red Piano, in Vietnam Symphony we see Communist leaders value and protect the classical musicians. You might like to choose to complete one of the sets of activities provided for each of the video clips.

The Red Piano is beautifully presented at the beginning and end with red and fawn patterned wrapping paper. It suggests the story within is a gift. In fact, the Koreans to the north of the setting of this story wrap many things in cloth. What else can you find out about this cultural practice?=

- HANDS-ON ACTIVITIES

Listening to piano music activities. Try to obtain CDs by Zhu Xiao-Mei, the artist whose story The Red Piano is based on.

Chops stamp activity. It is popular with tourists visiting China and Hong Kong to get one’s own stamp made. Such stamps are still used on legal documents, artworks etc. What else can you find out about the history of these stamps? Present your findings in a little red book format. See The Art of Chinese Chop (Seal) Carving: http://csymbol.com/stamp/chinese_chop_art.html <http://csymbol.com/stamp/chinese_chop_art.html

Ask the Art teacher to run a session on traditional Chinese water colour/ink-wash painting so students can try their hand.

- FURTHER RESOURCES

Screen Asia website

http://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/learning/screenasia/

Mao’s New Suit, 1997, filmed by Australian Sally Ingleton, in China. Ingleton follows two young Chinese women who were born during the Cultural Revolution. They remember their parents wearing blue Mao suits. They are creative designers in contemporary China and travel to Inner Mongolia to source fabric. A blog about the documentary is available on the internet, along with stills. http://australianscreen.com.au/titles/maos-new-suit/

Voices and Visions from China for the Senior English Classroom CD rom. Published by Curriculum Corporation, 2002. This is a rich resource of 40 multimedia texts which represent China’s past and present. Teachers should explore these buttons:-

Literature – especially Quiet Night, a poem by Li Bai, with moon imagery.

Film and Television – especially The Blue Kite and In the Heat of the Sun.

Popular Publishing – especially Physical Education poster.

Visual and Performing Arts – especially The White-Haired Girl, Traditional Music and Traditional Painting.

Background Briefing 19 July 2009 – Who stopped the music?

Summary: The parlous state of music in public schools means not only are our (Australian) children missing an important dimension in life, but they miss out on something that promotes brain function and social skills. Currently in Beijing, one million children are learning the violin. Across China it is estimated x million children are learning the piano.

http://www.abc.net.au/rn/backgroundbriefing/stories/2009/2612176.htm – 54k – [ html ] – 19 Jul 2009

Asia Scope and Sequence for English, SOSE and The Arts: http://www.asiaeducation.edu.au

ABC TV 7.30 Report, Mon 13/07/09: See story on a North Korean pianist who was imprisoned and tortured after being heard playing a French composer’s music to his girlfriend. Now free in South Korea, he enjoys playing piano where it is not an ‘instrument of the state’.

A Background to the Chinese Cultural Revolution

Joan Grant

The Lead up to the Cultural Revolution

There were great changes in China after the Communist Party’s victory in 1949. The previous Nationalist Government, headed by Generalissimo Chiang Kaishek, was authoritarian and corrupt, and there were huge disparities between the wealthy elite and the desperately poor peasants who were a vast majority of the population, which totalled some 580 million. Most peasants were illiterate, and girl children were often sold as slaves or concubines, if not killed at birth as unwanted burdens. The rigid education system, maintained from ancient times, sometimes allowed the brightest of peasant boys to be subsidised by their villages to study to become scholars and perhaps rise to positions of authority, but the difficulties of the language and the need to memorise large slabs of classical texts made this triumph extremely rare.

When the Communists, led by Chairman Mao Zedong, took over, they embarked on an ambitious program of social and economic reform. Individual peasants who had worked for landowners were incorporated into large “collectives” managed by Communist officials. The men and women ate together in large dining halls, often receiving more and better food than before, and attended numerous political meetings, where owners of local land or “rich peasants” were often attacked both verbally and physically as “capitalists” and “landlords” and many of them killed. During this period the Soviet Union supported the Chinese communists, sending many advisers and supplying aid and heavy equipment such as tractors.

The education system was modernised and extended to all children, with the aim of achieving 100% literacy. This aim was assisted by the simplification of complex Chinese characters, making classic texts unintelligible to most people, as Latin is to English speakers today. In a famous speech, Mao declared that “women hold up half the sky,” and girls and women were officially considered the equal of boys and men, in education, job opportunities and salaries. The Marriage Law permitted women to initiate divorce, which many did in the early days. Propaganda posters of the period show women as telephone linesmen, railway workers, forestry wardens, or in other jobs women had never done before. In practise though, equality was not easy to achieve, with the traditional family system of ancestor worship asserting that only males were important in maintaining the family line and good fortune. Health care was extended to large parts of the country, partly through the appointment of “barefoot doctors”, who had not had formal medical training. Mao also invited overseas Chinese to return and help to build a “new China”, and many did so, with teachers, scientists, artists and engineers flocking back to their homeland.

The Chinese Communists began to resent the Russians’ advice as “interference”, as the two countries became suspicious of each other’s aims, and after various disagreements they formally broke with the Soviet Union in 1960, sending all its advisors back to Russia. Mao declared China’s self sufficiency in all things, and instituted “The Great Leap Forward” which urged the population to make their own necessities, and produce such things as iron tools, ball bearings, and steel. Individuals created smelters in their back yards, melting down old pots and pans, but most of these attempts were failures, wasting huge amounts of raw materials. The government encouraged competition among individuals (creating “heroes of socialist labour”) and between factories and collectives, whipping up fervour which resulting in wildly exaggerated reports of amounts of grain harvested, goods produced, etc.

The birth of the Cultural Revolution

But Chairman Mao proved to be a better revolutionary leader than a guide for a nation in peace time. He believed that it was necessary to keep the population in a state of revolutionary enthusiasm to prevent people from relaxing and going back to old bourgeois ways, with some individuals getting richer and more powerful than others (of course, members of the Communist Party and Communist officials or team leaders, the “cadres”, or core workers, were more powerful than the rest, and did have special privileges). So in 1966 he initiated a campaign to re-revolutionise the population and emphasise “class struggle”, which came to be known as the Cultural Revolution.

It began in the schools where fanatical Young Pioneers (junior Party members) who believed that Mao was virtually a god, were given free access to the railways and encouraged to roam the countryside, attacking the “three olds” (old thought, old religion, old culture). They turned on their teachers, humiliating and beating them, and waved and quoted from The Little Red Book, a collection of Mao’s sayings. Temples and religious statues were torn down, books and paintings burned, schools and universities closed, and anyone who had lived overseas, had university education, owned houses or land, created Western-influenced art, music or writing, or was “an intellectual” was beaten, sometimes killed, or sent to the countryside to work with the peasants. This is what happened to most of those who had earlier come back to China at Mao’s call, to give their expertise to the nation. Anyone who had foreign connections was suspect, as were any Chinese who collected or performed Western art, literature or music, and roaming bands of young people attacked, tortured and often killed them. There were also pitched battles between groups of Red Guards and other activists, each of whom proclaimed themselves more “red” (or the others too “rightist” or “leftist”) than the rest. The country was in a state of chaos, and often fields were not harvested, and factories were idle, resulting in great deprivations for the people, including starvation. It is impossible to be exact, but certainly millions died during this period.

Many who were removed from their jobs and homes and sent to the countryside to “learn from the peasants” did manual labour for years, working to grow vegetables or in factories; others were sent to “re-education camps” where they did harsh work and studied Marxism-Leninism and Mao’s writings and wrote repeated self-criticisms. Children of parents sent to the countryside were sometimes allowed to accompany their parents, and worked with them in the fields or factories, but sometimes the children were left to fend for themselves in the cities, perhaps looked after by relatives or compassionate strangers, and many did not see their parents again for many years.

Most of those who didn’t die under the difficult conditions eventually returned to their former lives when the political climate changed after Mao died in 1976, and “The Gang of Four” who included Mao’s wife, Jiang Jing, and who were even more extreme in controlling the arts and the media (for instance, only “revolutionary” opera, music and art, which “served the people”, were permitted), were arrested, tried and jailed. Those who did return, for instance teachers, had to work in their former schools or universities, often with the people who had denounced and even beaten them.

Post Cultural Revolution China

However, even earlier than this, in 1972, there was the start of a relaxation as Mao and other officials tried to control what had been unleashed. President Nixon visited China in that year, and was greeted by Mao, and little by little there were visits by foreign journalists and businessmen, and then tourists and overseas Chinese visiting their relatives. Usually these people had no idea of what had been going on, as they were carefully watched and kept from mixing with ordinary people. Schools were reopened, and a small exchange of students began, with some Chinese students selected to study in the US or Britain and a few foreign teachers and students permitted to come to China. The first Australian students and teachers went to China in the early 1970s. Gradually life became more normal, although it took another ten years before an “open door” policy was announced, and people began gradually to take up their broken lives, begin to start their own small businesses and go to performances of Western artists or study abroad.

By the late 1970s, an Australian exchange teacher in Shanghai noted that at the conservatorium and concerts, Western music was beginning to be studied, played and listened to again, and musical instrument factories were manufacturing some European instruments as well as the standard Chinese ones. These days, there is a quite free exchange of students, teachers, businesspeople, artists, writers and scientists, and Western art and music are widely studied and played, with many Western orchestras and exhibitions available to the public throughout China. Even some of those who fled China as soon as they could after the Cultural Revolution, have come back to perform or work, although some who were political activists are still not allowed to return, even when parents die, or are afraid that if they do they will be at least deported, or perhaps arrested.

The Red Piano is published in association with Amnesty International

Australia.

Amnesty International is an independent worldwide movement of people who campaign for human rights to be respected and protected. Amnesty International has more than 2.2 million members and supporters in over 150 countries. Its supporters work together to promote a culture where human rights are embraced, valued and protected.

Amnesty International campaigns for all kinds of people, in all kinds of

situations, everywhere in the world – whether they be in the media’s spotlight or forgotten in a secret prison. To do this, the organization mobilises people, campaigns, conducts research and raises funds for its life saving work. We are promoting a culture where human rights are embraced, valued and protected.

Teaching for human rights: curriculum resources from Amnesty International Australia

“Human Rights today”

Amnesty International Australia’s curriculum resource “Human Rights today: Discussing the Issues, Accepting the Challenge” is aimed at teachers and students in years 9 and 10 and addresses human rights issues including:

- children’s rights

- Indigenous Rights

- the rights of women and girls

- human rights and conflict

- taking action for human rights.

The resource has been designed for teachers in the Studies of Society and Environment/Human Society and Its Environment/ Humanities area. It is also useful for teachers of English and Values Education, and teachers responsible for Civics and Citizenship Education. Each of the major themes is supported by a profile of a person who has defended human rights, such as Indigenous footballer Michael Long or anti-child labour campaigners Iqbal Masih and Craig Kielburger. The Taking Action section of the resource features practical ideas for what students can do (eg online action, creating posters on human rights, organising an event), each supported by guidelines and an example.

The accompanying webpage features:

- a downloadable chapter from the resource: ‘Tuning In to Human Rights’

- an online teacher guide

See www.amnesty.org.au/humanrightstoday

Curriculum resources on human rights in China

Amnesty International has also developed a set of materials on human rights in China, which can be viewed at

www.amnesty.org.au/humanrightstoday/comments/12526/

Themes include:

- Internet Censorship

- What is censorship

- Imprisoned for sending an email: the case of Shi Tao

- Internet censorship in China: “the Great Firewall”

- Human rights in China today: exploring some key issues

- Media freedom

- Human rights defenders in China

- The death penalty

- Fair trials, torture and imprisonment without charge

- Supporting Human Rights in China – What you can do.

China and human rights: other useful links

Entry on China from 2009 Amnesty International report http://report2009.amnesty.org/en/regions/asia-pacific/china

Amnesty International Australia China Campaign http://www.amnesty.org.au/china/

China: A snapshot http://www.amnesty.org.au/china/comments/11311/ features:

- Case studies: profiles of Chinese human rights defenders

- Research: What is internet censorship?, Who is affected by internet censorship?, The death penalty in China, Torture and detention without trial, Human rights defenders,

Human Rights Education webpage

Additional resources can be found at Amnesty International Australia’s human rights education page: http://www.amnesty.org.au/hre/

Extent: 40pp

Format: Hardback

ISBN: 9780980607017

First published in English by Wilkins Farago, September 2009

Advance Information Sheet

Press Release

Cover Image (100dpi jpg)

Cover Image (300dpi tiff)